Transgender issues in the Middle East

This is the second article in a four-part series which aims to give a broad but detailed overview of transgender issues in the Middle East.

- Part 1: Crossing lines

- Part 2: A history of ambiguity

- Part 3: Making the transition

- Part 4: Struggles for recognition

The complete series can also be downloaded as a printable 23-page PDF.

Part Two: A history of ambiguity

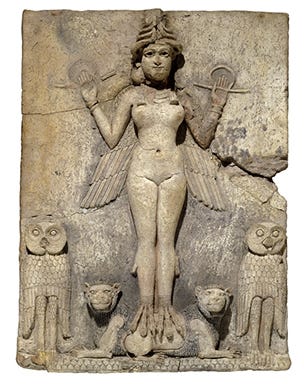

Ambiguities surrounding sex and gender have been recognised in many parts of the world over many centuries, and the Middle East is no exception. One of the most important deities of ancient Mesopotamia, in modern-day Iraq, was Ishtar, a goddess who represented both sexual attraction and war. Though female, Ishtar was sometimes depicted with a beard.

Little is known about the cult of Ishtar (also called Inanna in the Sumerian language) but a British Museum publication says of her:

She had the power to assign gender identity and could ‘change man into woman and woman into man’. Men called kurgarrus were followers of the cult of the goddess, and seem to have been considered woman-like men in some way … In one epic poem, the kurgarrus are people …

Whose masculinity Ishtar has turned into femininity to make the people reverend,

The carriers of dagger, razor, scalpel and flint blades,

Who regularly do [forbidden things] to delight the heart of Ishtar.While their gender was obviously regarded as in some way irregular, they were nevertheless part of the divinely ordained world order and of state religion.

When Islam emerged in the seventh century CE, rules for relations between the sexes started to become more formalised. Nevertheless, it was accepted that not everyone fitted neatly into a clear male/female binary. Rather than denying the existence of such people or treating them as an obstacle to social order, early Islam found ways of accommodating them — ways that did not threaten the system and even, to some extent, helped it function more effectively.

A verse in the Qur’an (24:31) acknowledges that not all men have the same sexual desires or capabilities. It begins by saying Muslim women should guard their modesty and not display their beauty to other men but then goes on to list men who are exempted from this rule: husbands, fathers, brothers, etc, plus — in the words of Yusuf Ali’s translation — male servants who are “free of physical needs”. Although the Arabic wording is rather cryptic the underlying principle is clear: it refers to men who, for whatever reason, can be expected not to take advantage of women sexually.

There were three types of people recognised as being outside the usual male/female binary: those whose sex was anatomically uncertain (traditionally known as hermaphrodites though the preferred term nowadays is “intersex”); eunuchs (castrated men); and mukhannathun — men who were regarded as effeminate.

The ‘hidden sex’ of a khuntha

A statement in the Qur’an that God “created everything in pairs” (51:49) forms the basis of an Islamic doctrine that everyone is either male of female — there can be no halfway house. The question this raised was what to do about children born with ambiguous genitalia since, according to the doctrine, they could not be sex-neutral.

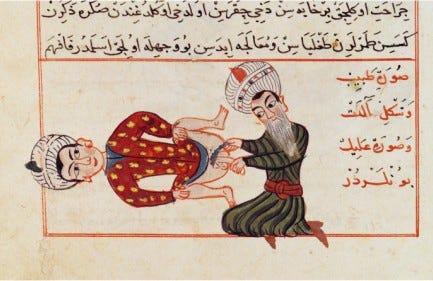

In establishing principles for ascertaining the sex of a khuntha — a person whose sex was unclear — a remark attributed to the Prophet about urine and the differing inheritance rules for men and women proved especially helpful. He is reported to have said that inheritance is determined by “the place of urination” (mabal, in Arabic).

To the jurists, this suggested a way of discovering a khuntha’s “hidden” sex. Thus the 11th-century Hanafi scholar al-Sarakhsi explained that a person who urinated “from the mabal of men” should be considered male and one who urinated “from the mabal of women” would be female. But the jurists also considered other eventualities, as Sanders explains:

If, however, the child urinated from both of the orifices, then the one from which the urine proceeded first was primary. If it urinated from both simultaneously, some said that primacy would be awarded to the organ from which the greater quantity of urine proceeded. Abu Ja’far al-Tusi, the Shi’a jurist, added another criterion: “If the onset of urination from [the mabals] is simultaneous, then [the sex of the child] is considered on the basis of the one that urinates last.”

If sex could not be ascertained during childhood there was still hope of clarifying the matter at puberty, with the development of secondary sex characteristics — beard, breasts, menstruation, ejaculation, etc. Failing that, the person became legally classified as khuntha mushkil (a “problematic” or “ambiguous” hermaphrodite) and the focus shifted away from body parts and towards accommodating the khuntha within a social system that was highly gendered.

In communal prayer, for example, it was established that a khuntha mushkil should stand behind the rows of men and in front of the rows of women. Sanders explains: “Should it [the khuntha] turn out to be a man, he would simply constitute the last row of men; should it turn out to be a woman, she would be the first row of women.”

As a precaution against invalidating the prayer, al-Sarakhsi advised that a khuntha should be veiled (in case the person’s “hidden” sex was female): “If it is a man, his being veiled is not forbidden in prayer, and if it is a woman, she is obliged to be veiled in her prayer.”

Similar rules applied after death. In the unlikely event that a man, a woman and a kuntha mushkil were buried in a common grave, the man’s body was to be placed closest to Mecca, followed by the kuntha and then the woman, with a partition of earth separating them.

For inheritance purposes, however, the khuntha was treated as female, and Sanders comments:

“The concern with maintaining both the boundary and the sexual hierarchy intersected with another concern that informed the negotiation of the jurists: protecting the male domain from intrusion … The supremacy of male over female was always asserted, and the superior position of the khuntha to women in prayer and burial customs was a way of maintaining the hierarchy in which men were, in relation to women, the superior party.

“When in doubt, the rule seemed to be to accord the inferior status to hermaphrodites. What was important was that access to the higher status of men be successfully protected. The rules assured that no hermaphrodite would attain the status accorded to men unless it could be demonstrated that he was, indeed, a man.”

Eunuchs: crossing and guarding boundaries

Unlike a khunta, the original sex of a eunuch (khasi in Arabic) was not in doubt. He was a man, but one who had been castrated, usually by the removal of his testicles. His penis might be removed too, though apparently that was less common.

Because eunuchs were assumed to be sexually inactive they were allowed access to the women’s quarters, as permitted by the Qur’anic verse quoted above. As a result, they acquired an important role in Muslim households that were wealthy enough to employ servants.

Since Islamic jurists disapproved of castration when performed by Muslims it is thought that eunuchs were usually acquired for non-Muslims as slaves. This might imply they had low status but their emasculation meant they were considered “safe” sexually and some of them certainly held positions of trust and influence. Baki Tezcan describes them as “emasculated guardians of political, sacred and sexual boundaries”.

Explaining the duties of the supervising eunuch in a Muslim household, Taj al-Din al-Subki, a prominent scholar during the Mamluk era, wrote:

“He is the one who is concerned with women. It is his duty and right to cast his eyes upon their affairs and to advise the master of the house [concerning them]. He must inform him [the master] of any suspicion which he himself is unable to clear, and he must prevent agents of debauchery such as old women and others from gaining access to the women [of the household].”

There is a story involving the Prophet, his concubine Marya, and a eunuch. Marya had been sent to the Prophet as a gift from the Byzantine Patriarch of Egypt. This aroused jealousy among the Muhammad’s wives and so Marya was installed separately from the Prophet’s household, on the outskirts of Medina where the Prophet used to visit her.

When Marya became pregnant and gave birth to a son rumours circulated that the Prophet was not the child’s father and suspicion pointed towards Marya’s Egyptian servant. The Prophet sent Ali (his cousin and son-in-law) to investigate. Doubts about the child’s paternity were resolved when Ali reported that the servant was a eunuch with neither penis nor testicles.

From the Umayyad period, and for several centuries afterwards, eunuchs also served in the palaces of Muslim rulers — again, presumably, because of the trusted status resulting from their emasculation. Others served as guardians of holy places in Jerusalem, Najaf (Iraq), Mecca and Medina. A few were reported to be still serving in Medina as recently as 2001, though their numbers had dwindled to 13 and there had been no new appointments since 1984.

Mukhannathun: the effeminate men of Medina

A third group who fell outside gender norms but proved more difficult for Islam to accommodate were the effeminate men known as mukhannathun (singular: mukhannath). In a paper on The Effeminates of Early Medina published by the American Oriental Society, Everett Rowson writes:

There is considerable evidence for the existence of a form of publicly recognised and institutionalised effeminacy or transvestism among males in pre-Islamic and early Islamic Arabian society. Unlike other men, these effeminates or mukhannathun were permitted to associate freely with women, on the assumption that they had no sexual interest in them, and often acted as marriage brokers, or, less legitimately, as go-betweens.

They also played an important role in the development of Arabic music in Umayyad Mecca and, especially, Medina, where they were numbered among the most celebrated singers and instrumentalists.

According to one description, the mukhannathun were men who resembled or imitated women in the “languidness” of their limbs or the softness of their voice. It’s unclear whether they also adopted a feminine style of clothing and, during the first century of Islam they were not associated with homosexuality (though later they were). They had a reputation for frivolity — which met with disapproval from devout Muslims — and some of them were renowned for making witty quips at the expense of the powerful or the pompous. The mukhannathun were generally not considered respectable and insulting someone by falsely calling him mukhannath was an offence punishable with twenty lashes.

In the hadith it is said that the Prophet cursed effeminate men (al-mukhannathin min al-rijal) and mannish women (al-mutarajjilat min al-nisa’) — a remark which is widely quoted today and provides a religious basis for laws against cross-dressing in numerous Arab countries.

However, reports from the hadith (collections of words and deeds attributed to the Prophet) need to be treated with caution: they have been handed down over generations and may have become garbled in the re-telling. Elsewhere in the hadith the Prophet is said to have condemned “men who imitate women” (al-mutashabbihin min al-rijal bil-nisa’) and “women who imitate men”. This may be a report of a different remark, or perhaps just a second version of the remark quoted earlier — which would raise the question of which version is correct.

Whatever the Prophet’s actual words, this is nowadays interpreted as a general indictment of effeminate men and masculine women but other evidence from the hadith suggests he never took action against them as a group. He does seem to have punished a few individual mukhannathun, though not necessarily for reasons connected with effeminacy.

One story concerns a man who had decorated himself with henna (normally a practice among women):

A mukhannath, who had dyed his hands and feet with henna, was brought to the Prophet.

The Prophet asked, “What is the matter with this one?”

He was told, “O Apostle of God, he imitates women.”

He ordered him banished to al-Naqi’ [a town about an hour’s walk from Medina].

They said, “O Apostle of God, shall we not kill him?”

He replied, “I have been forbidden to kill those who pray.”

This is the only story involving the Prophet where feminine behaviour by a man seems to have been the issue, and there is not enough detail to be sure whether henna was the problem or whether the man had been trying to pass himself off as a woman. If the latter, it’s easy to see why the Prophet might have decided to banish him: given the restrictions on contact between the men and women, people who disguised themselves as the opposite sex were probably engaged in some subterfuge.

Another story tells of the Prophet chastising a mukhannath who was also a singer, and in this case the issue was not the man’s effeminacy but his singing — an activity associated with immorality. The man reportedly came to the Prophet and said:

“O Apostle of God, God has made misery my lot! The only way I have to earn my daily bread is with my tambourine in my hand; so permit me to do my singing, avoiding any immorality.”

To this, Muhammad is said to have replied:

“I will not permit you, not even as a favor! You lie, enemy of God! God has provided you with good and permissible ways to sustain yourself, but you have chosen the sustenance that God has forbidden you rather than the permissible which He has permitted you.

“If I had already given you prior warning, I would now be taking action against you. Leave me, and repent before God! I swear, if you do it after this warning to you, I will give you a painful beating, shave your head as an example, banish you from your people, and declare plunder of your property permissible to the youth of Medina.”

Because the mukhannathun were assumed not to be interested in women they could be granted access — like the eunuchs — to places where men were not normally allowed. This gave them a role as matchmakers but also earned them a reputation as facilitators of illicit trysts and adulterous affairs.

Matchmaking is the subject of another story (which appears in the hadith in several versions) where one of the Prophet’s wives overheard a mukhannath recommending a woman to her brother with the words that “she comes forward with four and goes away with eight”. This is understood to mean that she had four wrinkles or folds on her belly, with ends that wrapped round to her back where they appeared as eight.

The mukhannath’s description resulted in the Prophet expelling him from the household and possibly banishing him into the desert. The reason seems to be that the mukhannath had been paying too much attention to women’s bodies (considering that mukhannathun were not supposed to be interested in them), or perhaps that passing this rather prurient description to another man defeated the purpose of keeping women in seclusion. Either way, it is clear that the mukhannathwas punished for what he did, not for who he was. In fact, this story provides the strongest evidence from the hadith that Muhammad did not punish mukhannathun as a group; the implication of the story is that the mukhannath would have continued having access in the household if he had not caused offence with his description of the woman.

For a time, the mukhannathun of Medina and Mecca enjoyed what Rowson describes as a position of exceptional visibility. This seems to have come to an abrupt and possibly violent end under the Caliph Sulayman (who reigned 715–17 CE). There are conflicting accounts of what happened but there is little mention of them in the sources until they re-appear during the Abbasid period, especially in Baghdad. By then, perceptions of them had changed. Rowson comments:

“A crucial factor was the sudden emergence of (active) homoerotic sentiment as an acceptable, and indeed fashionable, subject for prestige literature, as represented most notably by the poetry of Abu Nuwas.

“Increased public awareness of homosexuality, which was to persist through the following centuries, seems to have altered perceptions of gender in such a way that ‘effeminacy’, while continuing to be distinguished from (passive) homosexual activity or desire, was no longer seen as independent from it; and the stigma attached to the latter seems correspondingly to have been directed at the former as well, so that the mukhannathun were never again to enjoy the status attained by their predecessors in Umayyad Medina.”

The erotic dancers of Cairo

Jumping ahead to the 19th century, we find the mukannath traditions of Medina still alive among the erotic dancers of Cairo, some of whom were distinctly androgynous. In his book, “An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians”, the British orientalist Edward Lane gave a disapproving account, starting with the female dancers known as Ghawazee:

The Ghawazee perform, unveiled, in the public streets, even to amuse the rabble. Their dancing has little of elegance; its chief peculiarity being a very rapid vibrating motion of the hips, from side to side.

They are never admitted into a respectable hareem, but are not unfrequently hired to entertain a party of men in the house of some rake. In this case, as might be expected, their performances are yet more lascivious than those which I have already mentioned … I need scarcely add that these women are the most abandoned of the courtesans of Egypt.

According to Lane, many Egyptians had moral qualms about female dancers flaunting their bodies in this way but could ease their consciences if the dances were performed by feminine-looking men. These male dancers were known at the time as “khawwal” — a term used in Egypt today to refer to effeminate gay men. Lane’s account continues:

Many of the people of Cairo, affecting, or persuading themselves, to consider that there is nothing improper in the dancing of the Ghawazee but the fact of its being performed by females, who ought not thus to expose themselves, employ men to dance in the same manner; but the number of these male performers, who are mostly young men, and who are called “Khawals”, is very small. They are Muslims, and natives of Egypt.

As they personate women, their dances are exactly of the same description as those of the Ghawazee; and are, in like manner, accompanied by the sounds of castanets: but, as if to prevent their being thought to be really females, their dress is suited to their unnatural profession; being partly male, and partly female: it chiefly consists of a tight vest, a girdle, and a kind of petticoat.

Their general appearance, however, is more feminine than masculine: they suffer the hair of the head to grow long, and generally braid it, in the manner of the women; the hair on the face, when it begins to grow, they pluck out; and they imitate the women also in applying kohl and henna to their eyes and hands. In the streets, when not engaged in dancing, they often even veil their faces; not from shame, but merely to affect the manners of women.

They are often employed, in preference to the Ghawdzee, to dance before a house, or in its court, on the occasion of a marriage-fete, or the birth of a child, or a circumcision; and frequently perform at public festivals.

There is, in Cairo, another class of male dancers, young men and boys, whose performances, dress, and general appearance are almost exactly similar to those of the Khawals; but who are distinguished by a different appellation, which is “ Gink”; a term that is Turkish, and has a vulgar signification which aptly expresses their character. They are generally Jews, Armenians, Greeks, and Turks.

Oman: the man in a pink dishdasha

In her book, Behind the Veil in Arabia, Norwegian anthropologist Unni Wikan describes a chance encounter in Oman during the 1970s:

I had completed four months of field work when one day a friend of mine asked me to go visiting with her. Observing the rules of decency, we made our way through the back streets away from the market, where we met a man dressed in a pink dishdasha, with whom my friend stopped to talk. I was highly astonished, as no decent woman — and I had every reason to believe my friend was one — stops to talk with a man in the street …

No sooner had we left him than she identified him. “That one is a xanith,” she said. In the twenty-minute walk that followed, she pointed out four more. They all wore pastel-coloured dishdashas, walked with a swaying gait, and reeked of perfume. I recognised one as a man who had been singing with the women at a wedding I had attended recently. Another was identified as the brother of a man who had offered to be our servant — an offer we turned down because of this man’s disturbingly effeminate manners.

There were said to be about 60 xaniths in Sohar, the town where Wikan was doing her field work, among an adult male population of around 3,000 — two per cent of the total. There were also an unknown number of former xaniths, since it was possible to abandon the role as well as adopting it.

Since the ambivalent gender role of the khanith allowed them easy access to both male and female spheres they were highly employable as servants. They also worked as singers and, reportedly, by providing sexual services to men.

Wikan’s discovery proved controversial at the time, mainly because she went on to talk speculatively about “transexualism”, transvestism, homosexuality and a “third gender role”.

This led to some heated and equally speculative debate about the origins and exact nature of the xaniths in an anthropological journal with the strangely inappropriate title “Man”. Wikan’s critics variously questioned whether the xaniths were really Omanis, suggested they were the descendants of slaves or linked them to institutionalised prostitution in East Africa.

However, a closer look at the social history of Arabs and Islam would have made much of that debate unnecessary. Wikan’s term “xanith” is actually a quirky transliteration of khanith, derived from the Arabic triliteral root kh-n-th — a root which also provides the words kuntha and mukhannath. Thus, linguistically at least, there is no reason to regard the xanith/khanith of Oman as a foreign intrusion; they appear to be located firmly within Arabic-Islamic tradition.

Describing their appearance, Wikan writes:

[The khanith] is not allowed to wear the mask [face covering], or other female clothing. His clothes are intermediate between male and female: he wears the ankle-length tunic of the male, but with the tight waist of the female dress. Male clothing is white, females wear patterned cloth in bright colours, and xaniths wear unpatterned coloured clothes.

Men cut their hair short, women wear theirs long, the xaniths medium long. Men comb their hair backward away from the face, women comb theirs diagonally forward from a central parting, [khaniths] comb theirs diagonally forward from a side parting, and they oil it heavily in the style of women. Both men and women cover their head, xaniths go bare-headed.

Perfume is used by both sexes, especially at festive occasions and during intercourse. The xanith is generally heavily perfumed, and uses much make-up to draw attention to himself. This is also achieved by his affected swaying gait, emphasised by the close-fitting garments.

His sweet falsetto voice and facial expressions and movements also closely mimic those of women. lf xaniths wore female clothes I doubt that it would in many instances be possible to see that they are, anatomically speaking, male not female.

This dress code appears to have been developed with some precision and perhaps socially negotiated over time to place the khanith somewhere between male and female but without going too far in a female direction since, as Wikan points out, “cross-dressing” in Oman could be punished by imprisonment and flogging.

In legal terms the khaniths were regarded as men and referred to by others with masculine pronouns. Some also married, though after doing so they would be bound by the rules of gender segregation. The usual reason given for marriage was to have someone care for them and keep them company in old age. (Wikan adds: “Xaniths fetch their brides from far away, and marriages are negotiated by intermediaries, so the bride’s family will be uninformed about the groom’s irregular background.”)

Wikan’s account leaves unanswered questions about how and why some men chose to become a khanith: to what extent they may have been motivated by sexual orientation or gender identity, or how many of them simply viewed it as an occupation. The key point, though, is that while they existed outside the usual boundaries of male and female they were nevertheless accepted as part of Oman’s social fabric.

A gun-toting Iraqi woman

In contrast to effeminate men, recorded examples of “masculine” women — a female equivalent of the mukhannath — are comparatively scarce, perhaps because they were not considered worthy of note. But the boyat (tomboys) who have caused so much consternation in Gulf states during the last few years are clearly not the first of their kind. In the mid-1950s, while studying the Marsh Arabs of southern Iraq, German ethnologist Sigrid Westphal-Hellbusch and her husband, Heinz, discovered a class of women known as mustergil — a term which implies “becoming a man” or behaving like a man:

Many mustergil declare their decision to lead a manly life after their first menstruation … This decision is generally accepted without opposition by the community. The young girl, if she has not already begun to live like a boy, henceforth dresses as a man, sits together with the men in the meeting house, takes an active part in her own life, and procures weapons for herself to take part in hunts and war campaigns …

The acknowledgment of a mustergil as a man refers exclusively to her manner of life. She can never quite gain the status of a man, since no real estate can be bequeathed by her and any potential wealth she acquires is governed by the rules of inheritance for women, which differ from those for men.

Certainly it does happen that a mustergil, after some years of manly living, decides to marry … A mustergil marrying by her own choice, must completely break with her past; none of her former relationships in the men’s world survive, and, should her marriage take an unhappy course, she cannot return to her former manly life, for she is now, like other wives, bound to the marriage.

On the other hand, a wife can take up a manly life after the death of her husband. Such cases arise if a wife is willing to struggle alone with her children and to accept a man’s responsibilities along with a woman’s. For men’s work she would then adopt male clothing, obtain weapons for her protection, and thus be tolerated in the men’s world, especially if she proves to be self-reliant and gains the respect of her neighbours.

Writing* about the mustergil, Westphal-Hellbusch draws a very depressing picture of life as a marsh Arab woman in the 1950s — a life of exclusion and inferiority, of early (and often unhappy) marriage where her worth is measured by the number of male children she can produce. “It is not surprising,” Westphal-Hellbusch says, “that the wives become nagging, embittered, unobliging, and ugly inside and out; calm, affable wives are an infrequent exception.”

There were thus plenty of reasons why a woman might choose not to marry and become a mustergil instead. Possibly this institutionalised form of gender-bending served as a social safety valve: allowing the most disaffected women to adopt a male lifestyle (so long as they also accepted the responsibilities of manhood) may have helped to protect this highly patriarchal system from serious challenges.

However, Westphal-Hellbusch notes that there were “frequent cases” of women adopting a male role out of economic necessity rather than choice, citing the story of a labourer who at first sight appeared to be a young man but when examined by a doctor turned out to be female. The explanation given was that she was an only child who had taken up labouring to support her parents.

At the upper end of the social scale, though, Westphal-Hellbusch became acquainted with a female poet “from one of the richest sheikh families of lower lraq” who had apparently chosen to live as a man for different reasons:

First, she is moderately deformed and very small, which was surely a major hindrance to marriage, although she does not speak about it; and second, she hates her father because of certain personal experiences; on this she speaks and produces poetry at every opportunity.

The woman, who was not identified by name and claimed to be one of about 50 mustergil women in her clan, carried a rifle and revolver in her village but dressed as a man only from the neck downwards. On her head, a hijab covered her long hair. Westphal-Hellbusch explained:

She retains these outward marks distinguishing her sex because she prays to Allah every day and has to do so as a woman or else her prayers would be of no consequence …

She is an actively religious person [judging by her location, presumably Shia] and has irrevocably decided to deny her family any part of her inheritance after her death by donating her land and possessions to a high religious official who will then do good deeds for the poor in her name.

The woman seemed to have adopted God as a surrogate father-figure because of a turbulent family background which included the murder of her mother by the family of her stepfather. This had led her to hate men in general but, in Westphal-Hellbusch’s words, “did not dissuade her from being like a man; indeed, she wanted to be more like a man”. In this she had been remarkably successful, achieving the highly unusual feat (for a woman) of having her family land signed over to her: “It is a source of great satisfaction to her that the land legally belongs to her; she is a man.”